COVID-19 day 123 : 📈 1,601,434 cases; 96,007 deaths : 22 May 2020

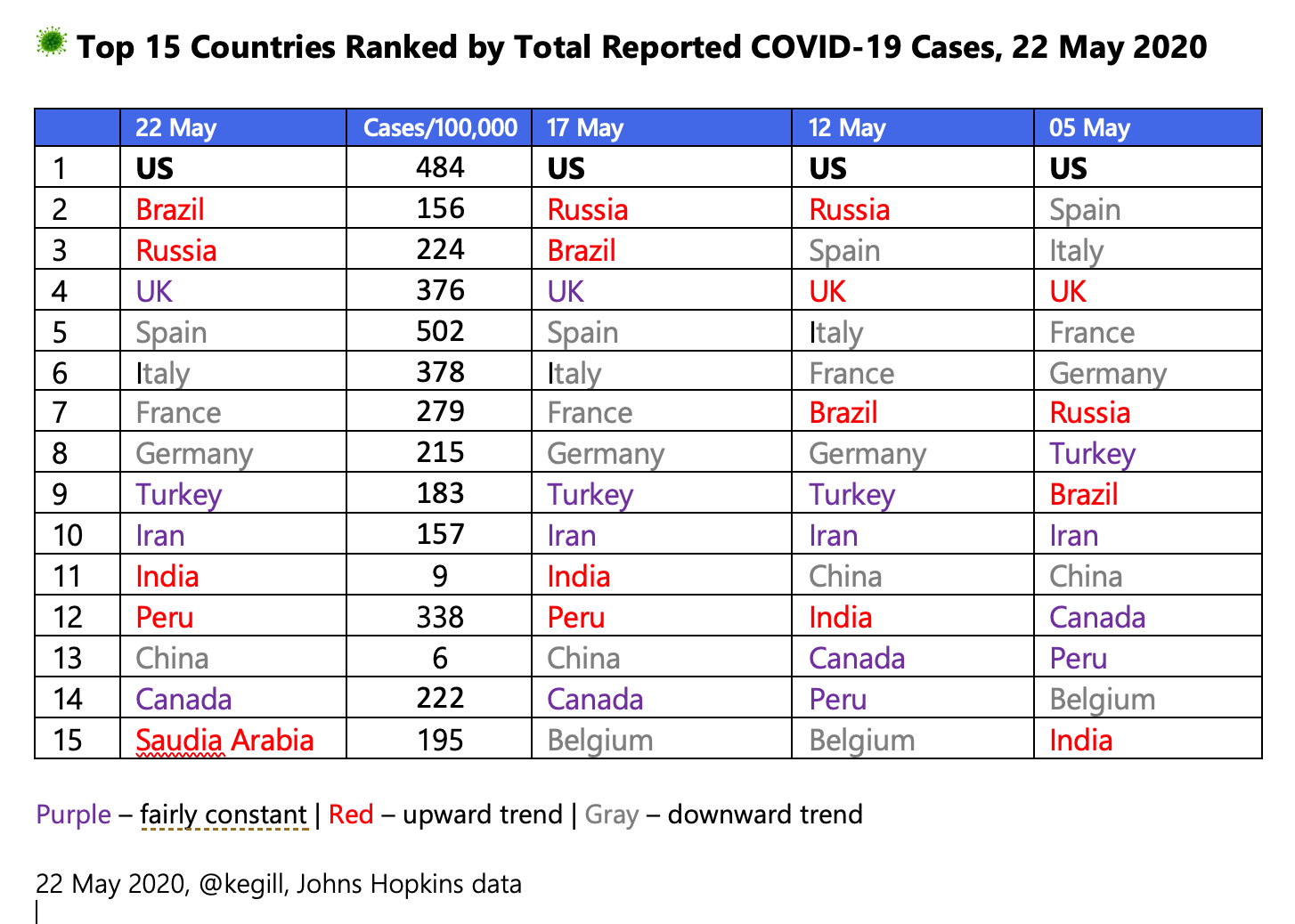

One big thing: news media need to use a "truth sandwich" when reporting political pronouncements related to COVID-19; Brazil, the 4th largest nation, now second to US in identified cases

It’s day 123 since the first case of coronavirus disease was announced in the United States. We have 1.6 million cases and 96,000 deaths. Welcome to a second “disinformation” edition.

⓵ One big thing

Three or four people sitting around talking about news events is not news. It’s opinion. [It’s also a helluva lot cheaper to produce than news stories filling the same air time.]

The op-ed section of newspapers and magazines (print or online) is not news. It’s opinion.

By definition, opinion has a point of view. Opinions are not neutral.

Straight news stories focus on who, what, when, where, how and why (WWWWHW) [1]. These questions get increasingly difficult to answer as you work through them sequentially. Why is the stuff that keeps detectives, investigators and mystery novelists up at night.

The first paragraph (the lede) or opening soundbite is crucial for setting the stage for a story. In straight news, the writer tries to answer as many of those questions as possible, in an even-handed manner. A “neutral” stage.

The straight news formula may work fine for routine car accidents, fires, trial results, stories where facts are not disputed. The sky is dark at night (maybe).

Most of what passes as “TV news” today - and much of what happens in “print” (textual-based reporting) abandoned WWWWHW eons ago.

Very little about COVID-19 is “straight news” and very little is neutral.

For example, reporting daily COVID-19 death counts is straight news. A form of stenography. Big numbers create drama.

Reporting in terms of per capita deaths or seven-day moving average or compared to another jurisdiction or country, is more valuable to the reader (context) but is inching towards analysis. It takes longer. It may not be as sexy or generate as many clicks.

Case study. This Washington Post story looks like straight news:

The coronavirus [who] may still be spreading at epidemic rates [what] in 24 states, particularly in the South and Midwest [where], according to new research that highlights the risk of a second wave of infections [what] in places that reopen too quickly or without sufficient precautions [where].

But here’s the next paragraph:

Researchers at Imperial College London [who] created a model [what] that incorporates cellphone data [how] showing that people sharply reduced their movements after stay-at-home orders were broadly imposed in March [when]. With restrictions now easing and mobility increasing with the approach of Memorial Day and the unofficial start of summer, the researchers developed an estimate of viral spread as of May 17 [what].

Two key words in this paragraph: “model” and “estimate.”

This is clearly newsworthy information.

But how many lay people have the skills, knowledge and wherewithal to analyze how methodologically sound that research and the resultant model might be?

< 🦗🦗🦗🦗🦗>

Case study: the Santa Clara County research pre-print claiming that the coronavirus infection rate was far greater (more asymptomatic cases) than public health experts had been (still are) estimating.

Where did this “news” get legs? In part, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed (Friday, 17 April 2020, 4:28 pm ET, paywall) which ran the same day that the research was published on a pre-print server. And FOX News, of course.

There were many use-the-news-release to write a “straight” news story that Friday as well (e.g., CNBC, Palo Alto CA, The Guardian).

Over on the digital water cooler that is science Twitter, peers were far more skeptical.

So were other public heath officials.

Not only do most of us lack the knowledge to assess that study, most reporters lack that knowledge as well. They were trusting the reputation of the institution (Stanford) and the researchers. Besides, there was a news release.

Not disclosed: funding. (And apparently no reporters asked.) The study seems to have been partially funded by JetBlue’s founder, someone with a “vested interest in any research that makes the case that the lockdown is an overreaction.”

Postmortems (op-eds) acknowledged scientific pushback, weeks later.

What followed next was the academic version of a roast, with critics raising issues with the researchers’ recruitment method (Facebook ads), flaws in their statistical methods, and even the tests themselves—manufactured in China, and since banned from export.

A lack of the personal knowledge needed to assess truth (and risk) is why we rely on experts. The world is becoming more unknowable at the same time a growing number of us say we do not trust experts (analysis, op-ed, interview with author and the book).

I’ve seen no news organization release a mea culpa, apologizing for amplifying a news release. That’s because in the Santa Clara County study, reporters treated coronavirus research like any other “news” story.

In the process, they did a disservice to public heath because they “flooded the [news] zone with 💩” (Steve Bannon, 12 Feb 2018). The results were then politicized by those opposed to stay-at-home orders. Op-ed. A month later.

Take-away: even before COVID-19, news media didn’t have a good track record for reporting health research. Now is the time for them - and us as news consumers - to be more skeptical, not less. This research isn’t “breaking” news but it’s been treated as though it were. Being first to amplify non-peer reviewed research is not unlike being the first report a disaster: truth is lost in haste.

Politicians are not neutral actors

When the WWWWHW formula is used to “report on” politicians making pronouncements (often just an opinion, sometimes factually wrong) it often leads to “he said, she said” stories (an odd form of stenography) with no judge present.

Thus when reporters treat political pronouncements as “straight news” they risk perpetuating deception, propaganda and lies.

Enter cognitive linguist George Lakoff (Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate), who argues that statements that would flunk a fact-check should not be treated like straight news.

Instead, the story structure should use a “truth sandwich” (aka “reality, spin, reality”).

Open with a statement of truth. “Always frame the truth first, because framing first establishes an advantage.”

Call out the lie. Don’t “[amplify] the exact language.”

Repeat and reframe the truth. Always repeat the truth more than the lie.

Today’s truth sandwich from Jay Rosen responds to Trump’s latest attempt to “flood the zone with 💩.” He is economical with words; the lede fits a tweet.

What can we do?

First, be aware of framing and our reactions. When the urge to share without thinking strikes, hit pause instead. No time to check it out? Use digital notepaper to save the article, tweet, Instagram or Facebook post, YouTube video.

Second, be skeptical of feel-good promises, whether from a politician or from a researcher. This is a long game, and our worlds may forever be changed.

Third, rather than share something based on an emotional response, use the Jay Rosen model. Rewrite and share the story as a short #truthSandwich. (I would LOVE to see this become a trending hashtag!) It is not easy, but it is rewarding.

Unlike taking hydroxychloroquine, the answer to “what have. you got to lose if you do this” really is “nothing.” Well, nothing but a feeling of impotence.

At its heart, a truth sandwich elevates truth over accuracy. In the long run, it might help reverse eroding public trust in experts and maybe serve as a ripple that improves journalism. It might even jumpstart the recovery of public discourse.

Seriously, what have we got to lose?

[1] Yes I know it’s taught as who, what, when, where, why and how. I think why is the more difficult question, so for the purpose of this essay, I moved it to the end!

Image quote from The Atlantic.

⓶ Politics, economics and COVID-19

President Trump has amplified the possibility that hydroxychloroquine might be effective in treating COVID-19. A study published today in The Lancet, one of the oldest and best-known general medical journals in the world.

Mandeep Mehra, MD, of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston and one of the researchers, said in a statement:

This is the first large scale study to find statistically robust evidence that treatment with chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine does not benefit patients with COVID-19.

This observational study found the drugs to be “associated with a higher risk of death in the hospital and serious heart rhythm complications.”

Please take a moment and share this newsletter with two other people! ✅

⓷ Case count

🦠Friday, Johns Hopkins reported 1,601,434 (1,577,287) cases and 96,007 (94,702) deaths in the US, an increase of 1.53% and 1.38%, respectively, since Thursday. A week ago, the daily numbers increased by 1.80% and 1.93%, respectively.

The seven-day average: 22,577 (22,771) cases and 1,206 (1,257) deaths

Percent of cases leading to death: 6.0% (6.0%).

Today’s case rate is 483.81 per 100,000; the death rate, 29.00 per 100,000.

One week ago, the case rate was 436.07 per 100,000; the death rate, 26.46 per 100,000.

Note: numbers in (.) are from the prior day and are provided for context. I include the seven-day average because dailies vary so much in the course of a week, particularly over a weekend.

There is a lag between being contagious and showing symptoms, between having a test and getting its results. The virus was not created in a lab and the weight of evidence is it was not released intentionally. Although early reports tied the outbreak to a seafood (“wet”) market in Wuhan, China, analyses of genomic data in January suggested that the virus might have developed elsewhere.

🌎 22 May

Globally: 4 993 470 cases (100 284 new) with 327 738 deaths (4 482 new)

The Americas: 2 220 267 cases (54 264 new) with 131 605 deaths (2 956 new)

Johns Hopkins interactive dashboard (11.00 pm Pacific)

Global confirmed: 5,213,557 (5,106,155 - yesterday)

Total deaths: 338,232 (332,978 - yesterday)

Recovered: 2,058,237 (1,950,518 - yesterday)

🇺🇸 22 May

CDC: 1,571,617 (20,522) cases and 94,150 (1,089) deaths

Johns Hopkins*: 1,601,434 (1,577,287) cases and 96,007 (94,702) deaths

State data*: 1,591,475 (1,568,372) identified cases and 90,156 (89,006) deaths

Total tested (US, Johns Hopkins): 13,398,624 (13,056,206)

View infographic and data online: total cases and cases and deaths/100,000.

* Johns Hopkins data, ~11.00 pm Pacific.

State data include DC, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands

⓸ What you can do

Stay home as much as possible, period.

Digestive problems may be a symptom.

Resources

👓 See COVID-19 resource collection at WiredPen.

📝 Subscribe to Kathy’s COVID-19 Memo :: COVID-19 Memo archives

🦠 COVID-19 @ WiredPen.com

🌐 Global news

📊 Visualizations: US, World