A case for a universal basic income

The problem is more than "artificial intelligence."

Headlines and pundits bemoan forthcoming job losses due to corporate adoption of “artificial intelligence.”* Forget that for a moment, because household name corporations are killing jobs in real time.

In Lexington, NE, a town of about 11,000, Tyson Foods has announced it is closing its 35-year-old meat packing plant this month and is laying off 3,200 workers.

On the east side of the country, Jim Beam is suspending distillery operations for a year at its Clermont, KY (population less than 500) facility effective January 1st. No layoffs have yet been announced by its Japanese owner, Suntory Global Spirits.

Nationally, companies cut 1,170,000 jobs in 2025, the most since Covid in 2020. For example, thousands of employees at Intel, Meta, Paramount, Salesforce and Walt Disney Co. lost their jobs in 2025. Microsoft laid off 15,000. Amazon, 14,000 “corporate roles.”

Probably no layoff has been as devastating to a community as Tyson’s decision about Lexington.

“Losing 3,000 jobs in a city of 10,000 to 12,000 people is as big a closing event as we’ve seen virtually for decades,” Michael Hicks, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Indiana’s Ball State University, told Associated Press.

“The atmosphere inside the Tyson plant, where workers process as many as 5,000 head of cattle a day, laboring on slaughter floors, cleaning crews or trimming cuts of meat, feels ‘like a funeral,’ [Lizeth Yanes] said...

“The school district, where at least 20 languages and dialects are spoken, has higher high school graduation and college attendance rates than the state and national average, and one of Nebraska’s biggest marching bands. Residents are proud of the diversity and the tightknit community, where young people return to raise families.”

Lexington is a small community where the loss of 3,200 jobs will ripple through to “thousands of jobs in related sectors.” Researchers at the University of Nebraska predict the closure will cost the state almost $3.3 billion annually. Total job losses estimated at 7,000.

Oh, and the company pays no city taxes. Its CEO, Donnie King, earned 51% more in 2025 than 2024, despite losing a billion dollars in the company’s beef business.

Many Tyson employees have worked nowhere else. Some do not speak English. There are not 3,000 jobs just hanging around, waiting for employees with limited computer skills.

Most workers will have to leave Lexington unless Tyson figures out something else to do with the facility, or they sell it to another meat packer. (A sale is unlikely in this short beef supply situation, where, when the year began, the US had the lowest number of cattle since 1951. We have twice that population today.)

Unemployment insurance is a worker’s only stopgap, a “safety net.” However, many of these employees are over 50. Their chances of finding a job with an equivalent income are slim, even should they relocate.

Enter universal basic income (UBI). UBI is intended as a basic floor for adults and has no requirements.

Maybe in the case of layoffs, some of the UBI funds should come from the corporation. After all, the Tyson CEO compensation for 2025 was $34,469,000. Not the c-suite: the CEO, alone.

What is coming in Lexington are permanent job losses for people not yet 65. This seems like a population for testing UBI despite automation being a favorite bugaboo. From Stanford:

The growth of income and wealth inequalities, the precariousness of labor, and the persistence of abject poverty have all been important drivers of renewed interest in UBI in the United States. But it is without a doubt the fear that automation may displace workers from the labor market at unprecedented rates that primarily explains the revival of the policy…

Lexington, NE is an ideal pilot because areas where UBI will probably be more necessary, soon, are America’s rural and ex-urban areas.

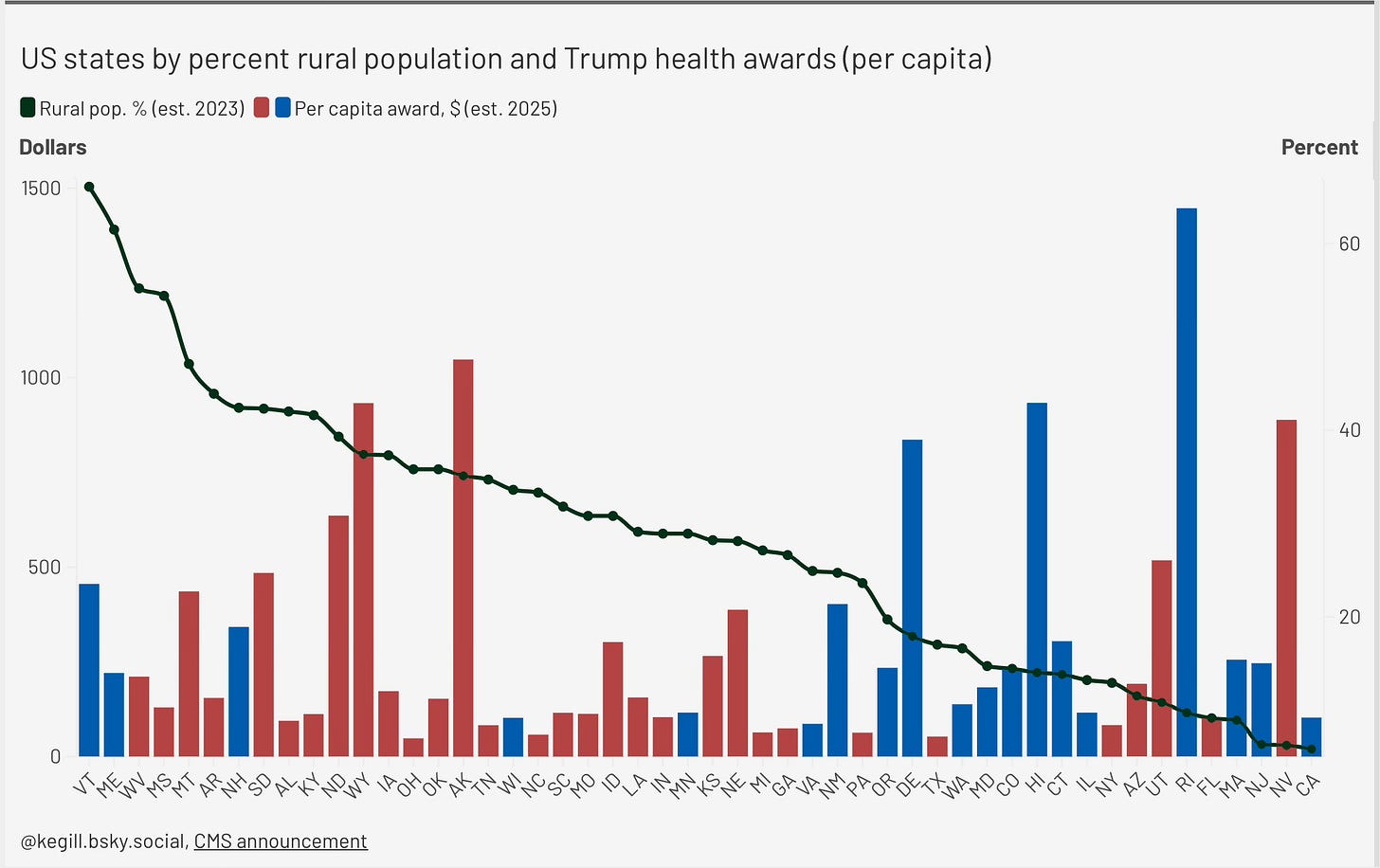

Look at the estimated losses in health care in 2026: $125 billion for rural communities (due to Medicaid Medicare cuts plus ACA tax credit expiration). That’s about $1,770 per capita (estimated rural population). The Trump Administration, through the BBB, is offering communities only $47 to $1,447 per capita to support rural health care. (Only two states are in four digits, Rhode Island and Arkansas; 11 are in two digits.)

I was surprised to learn that Milton Freedman was a proponent of a form of UBI through a negative income tax credit. Many Americans first heard of the concept years later when Andrew Wang ran for president.

I do not know enough about other federal programs for poverty to discuss whether or not a UBI should replace programs like food stamps (SNAP) or USDA’s Women, Infants and Children program.

Unlike most UBI proponents, I think there should be an income cap. That cap would need to be related to cost of living and average wages in a person’s hometown area. You can’t honestly equate Lexington NE and Lexington KY (population 11,000 v. 320,000) in job opportunities, average wages or cost of living.

We have ongoing guaranteed income pilot projects across the country. None come close to the scale of the disaster awaiting Lexington, NE.

Cities in Africa, Asia, and Europe are also experimenting with guaranteed basic income programs. South Korea is focusing on farmers and fishermen. Wales is focusing on youth coming out of the foster care system. “Unconditional cash transfers to women” are proliferating across India. Give Directly launched in Kenya in 2016.

We must plan for a world where there are far more adults than jobs. That world cannot afford billionaires (or a trillionaire). The time for UBI has come, despite today’s do-nothing federal government. Talk to your Congress folk. Change requires awareness, usually via squeaky wheels.

~~~

* “Artificial intelligence” uses algorithmic probability to create words, images and voice based on information used to develop those probabilities, usually without regard to copyright owner rights. It’s not intelligent and cannot think.

The Lexington case study powerfully illustrates structural displacement that existing safety nets weren't designed to address. Your point about distinguishing between AI-driven speculation and actual corporate consolidation is important - the Tyson closure represents capital mobility choices rather than technological inevitability. The scale matters: losing 3,200 jobs in a town of 11,000 creates cascading effects that unemployment insurance alone can't mitigate. Your suggestion about means-testing UBI based on local cost-of-living indices is pragmatic and addresses concerns about universality versus targeting. The comparison with rural healthcare funding gaps also highlights how current support systems operate at mismatched scales. One implementation question: should UBI pilots in places like Lexington include clawback provisions tied to employers who extract value then exit communities? The CEO compensation disparity you cite (51% increase while closing facilities) suggests that social insurance costs might reasonably be distributed differently when corporate decisions drive displacement.